| Thrust

Before the airplane begins to move, thrust must be exerted. It

continues to move and gain speed until thrust and drag are equal. In order to

maintain a constant airspeed, thrust and drag must remain equal, just as lift

and weight must be equal to maintain a constant altitude. If in level flight,

the engine power is reduced, the thrust is lessened and the airplane slows down.

As long as the thrust is less than the drag, the airplane continues to

decelerate until its airspeed is insufficient to support it in the air.

| Likewise, if the engine power is increased, thrust becomes

greater than drag and the airspeed increases. As long as the thrust

continues to be greater than the drag, the airplane continues to

accelerate. When drag equals thrust, the airplane flies at a constant

airspeed.

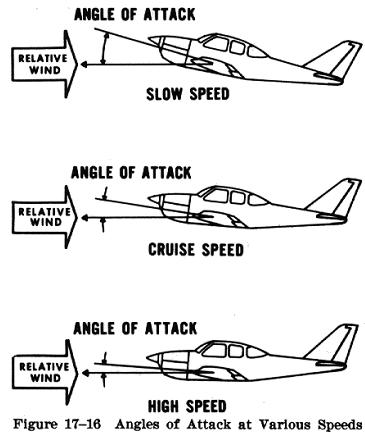

Straight and level flight may be sustained at speeds from

very slow to very fast. The pilot must coordinate angle of attack and

thrust in all speed regimes if the airplane is to be held in level flight.

Roughly, these regimes can be grouped in three categories; low speed

flight, cruising flight, and high speed flight.

When the airspeed is low, the angle of attack must be relatively high

to increase lift if the balance between lift and weight is to be

maintained (Fig. 17-16). If thrust decreases and airspeed decreases, lift

becomes less than weight and the airplane will start to descend. To

maintain level flight, the pilot can increase the angle of attack an

amount which will generate a lift force again equal to the weight of the

airplane and while the airplane will be flying more slowly, it will still

maintain level flight if the pilot has properly coordinated thrust and

angle of attack.

Straight and level flight in the slow speed regime provides some

interesting conditions relative to the equilibrium of forces, because with

the airplane in a nose high attitude there is a vertical component of

thrust which helps support the airplane. |

| For one thing, wing loading tends to

be less than would be expected. Most pilots are aware that an airplane will

stall, other conditions being equal, at a slower speed with the power on than

with the power off. (Induced airflow over the wings from the propeller

contributes to this, too.) However, if we restrict our analysis to the four

forces as they are usually defined, one can say that in straight and level slow

speed flight the thrust is equal to drag, and lift is equal to weight.

During straight and level flight when thrust is increased and

the airspeed increases, the angle of attack must be decreased. That is, if

changes have been coordinated, the airplane will still remain in level flight

but at a higher speed when the proper relationship between thrust and angle of

attack is established.

If the angle of attack were not coordinated (decreased) with

this increase of thrust the airplane would climb. But decreasing the angle of

attack modifies the lift, keeping it equal to the weight, and if properly done,

the airplane still remains in level flight. Level flight at even slightly

negative angles of attack is possible at very high speed. It is evident then,

that level flight can be performed with any angle of attack between stalling

angle and the relatively small negative angles found at high speed.

|

FAATest.com

- Aviation Library

Dauntless

Software hosts and maintains this library as a service to pilots

and aspiring pilots worldwide. Click

here for ways to show your appreciation for this service.

While much of this material comes from the FAA, parts of it are (c) Dauntless Software, all rights reserved. Webmasters: please

do not link directly to individual books in this library--rather,

please link to our main web page at www.dauntless-soft.com or

www.faatest.com. Thanks! |

|